Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem

Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem

Christmas is traditionally a time for family and friends getting together and for exchanging gifts. Among my extended family and close friends, Muslim and non-Muslim, both will be done. And both sides of the Tasman are involved.

An uncle from Los Angeles visited Australia for the first time and his wife convinced me to take both of them to New Zealand. Our trip coincided with the Sydney beach riots which made my relatives particularly desperate to leave Sydney although I joked: "Hey, you guys must be used to that sort of thing, coming from LA".

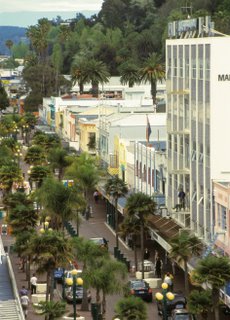

Napier, New Zealand

We were in New Zealand for five days, only enough time to drive a circle around the North Island. Despite our requests, my mother and aunt refused to remove their headscarves. As if the rioters were crossing the Tasman to cause more trouble. The closest we did come to cultural conflict was walking down the main street of Napier in search of breakfast. I noticed the locals staring. Naturally, I presumed the ladies' defiance over their headscarves was disturbing.

Then one of the locals shouted the real cultural reason for the stares. "Why are you wearing that damned Wallabies' jersey in New Zealand?"

Before leaving for New Zealand, I decided to deliver my Christmas gifts early. One recipient of this clean-shaven Islamic Santa's largesse was a Kiwi friend of mine who never met her Muslim dad. This year she will receive a package of three books, including a selection of Rumi poems and the latest Deepak Chopra offering.

As usual, I will spend Christmas Day having lunch with my best mate. We both attended Sydney's only Anglican Cathedral School. Some years back, I introduced him to a Japanese friend. They instantly clicked. I was best man at their wedding.

It was a truly Australian event - an Anglican boy marrying a Buddhist girl with a Muslim best man, all taking place at St Andrews Cathedral.

At age 14, I was given my first translation of the Koran in English, a very old version first published in Lahore during the 1930s and made by a high-ranking Indian civil service named Abdullah Yusuf Ali. The Jesus story can be found in a chapter of the Koran named "Maryam" (Arabic for Mary).

It begins with the usual supplication that commences all but one chapter: "In the name of God, Most Gracious and Most Merciful".

This supplication is used not only when commencing a reading of the Koran, but precedes virtually all the daily actions of a Muslim, both mundane and devotional.

The chapter describes how John the Baptist appeared on the scene. John (named Yahiya in classical Arabic) was born to Zachariah, and both father and son are revered as prophets. Once John has been mentioned, Mary is introduced. She is described as withdrawing from her family "to a place in the East". A messenger from God appears in her private chamber announcing she shall have the gift of a holy son.

Mary: How shall I have a son, seeing that no man has touched me, and I am not unchaste?

Angel: So it will be: Thy Lord saith: "That is easy for Me: and We wish to appoint him as a sign unto men and as a Mercy from Us". It is a matter so decreed.

Following the birth, Mary took her son back to her family. Her father was a respected rabbi and Mary was always known for her modesty and chastity. When she was first publicly accused of sexual impropriety, she pointed to the baby Jesus.

The Koran describes the first miracle of Christ - his speaking from the cradle in defence of his mother.

His exact words were:

"I am indeed a servant of God: He hath given me revelation and made me a prophet. And he hath made me blessed wheresoever I be, and hath enjoined on me prayer and charity as long as I live.

"He hath made me kind to my mother, and not overbearing or miserable. So peace is on me the day I was born, and the day I die, and the day I shall be raised up to life again."

A number of Jesus' other miracles are mentioned in the Koran, as is Christ's ascension. It is not surprising then that in the place where it all happened, the Palestinian town of Beit Lahm (Bethlehem), Muslims and Christians both celebrate Christmas.

In many Muslim countries, Christmas is a public holiday. And when Christian leaders remind us that "Jesus is the reason for the season", our Muslim brethren should find nothing objectionable in this.

Christmas should remind us that, despite cultural and theological differences, the things that unite us are greater and more important than those which divide us.

(First published in the New Zealand Herald on December 22, 2005.)