Today, Baghdad is a city in ruins. Almost daily, we watch TV news of another suicide bombing in which more innocent lives are lost to some wacko form of 'jihad'. But were things always this bad?

Some 900 years ago, Baghdad was the centre of civilisation. Europe may have been struggling out of its Dark Ages, but Baghdad was experiencing a Renaissance.

It was around this time that a great Baghdad jurist named Abdul Qadir Jilani appeared. Jilani is regarded as one of Islam's greatest legal scholars. Yet this Christ-like figure also spent many years in the wilderness searching for the real meaning of life. He found it in the mystical traditions of Sufism.

In his classic work, Fayuz-i-Yazdani, we read the following:

Once a person said to a dervish, 'All I ask for is a small dwelling in Paradise.' The dervish replied, 'If you displayed the same contentment with what you already have in this world, you would have found ultimate bliss.'

Sufis were not escapist mystics hiding in caves and escaping from the world — they believed that the path to God lay in the struggle for justice and truth, and that the highest state of spirituality was not achieved by total immersion in the Divine Being, but through service to one's fellow human beings.

We often hear of modern politicised 'Islamism' — a term devised by veteran islamophobe Daniel Pipes to describe a modern political ideology which co-opts the religious terminology and symbols of Islam to achieve essentially political ends. But for neo-Conservatives like Daniel Pipes and Mark Steyn to claim Islamic religion must always be kept separate from politics is the height of hypocrisy. In reality, 'Islamism' is little more than neo-Conservative Islam.

Many neo-Cons use the language of Biblical Zionism and Armageddon to foment a clash of civilisations. Similarly, the nutcases from al-Qaeda and other fringe groups use Islamic theology and its symbols to fight their war against anything they deem against their vision for the world.

What both the American and Muslim neo-Cons have in common is a deep-seated hatred for Muslims. If you don't believe me, read Pipes's article 'Two Opposite Responses to Terrorism', published in the tabloid New York Post on 14 September, 2004.

The article's thesis is simple. When Nepalese civilians in Iraq are kidnapped by dissidents, members of the majority Nepalese Hindu community lynched their Muslim countrymen, burnt their shops and destroyed their homes. Nepalese civilians were then released. The French, on the other hand, respond to kidnappings of their nationals in Iraq by sending French Muslim delegations and other peaceful means. These didn't work and French nationals were killed.

The moral of the story? The best way to fight Iraqi dissidents and secure the release of your nationals is to persecute your Muslim minority. Basically, bring on another Cristalnacht. How such a hate-filled article could have found its way into the otherwise sober Melbourne Age beats me. Both in aims and results (race-hatred, terror and repression) there is very little difference between between Pipes's prescription and the activities of al-Qaeda, Jemaah Islamiyah and al-Zarqawi.

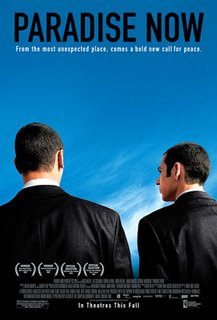

That is the macro-theory. What about the micro-reality? How can these fringe Muslim movements convince young people to adopt suicide as a religiously mandated option when their entire theology is based on living and struggling even when the odds are stacked against them? Perhaps this is where the recent movie Paradise Now becomes essential viewing. This is not a movie to watch on a sunny Sunday afternoon. Or maybe it is, because that's when a friend and I watched it.

Perhaps this is where the recent movie Paradise Now becomes essential viewing. This is not a movie to watch on a sunny Sunday afternoon. Or maybe it is, because that's when a friend and I watched it.

My friend is of South Indian Tamil background. I am of North Indian Muslim background. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were most successful in using suicide bombing as a weapon, and their methods were adopted by terrorist groups masquerading as 'Islamic movements' — HAMAS, Islamic Jihad, al-Qaeda, Jemaah Islamiyah — and, it seems, second and third generation North Indian and Pakistani boys in Leeds and London … and Iraqis and Jordanians and others responsible for the recent bombings in Jordan.

Not a single bomb goes off in the 90 minutes of this movie. A few images were shown of young men being shot at by soldiers.

For the most part, the movie centred upon a few characters. There is Suha (played by Lubna Azabal), the middle-class daughter of a Palestinian hero. She has arrived in the West Bank town of Nablus after spending years studying in France and Morocco, and speaks Arabic with a distinctly cosmopolitan North African accent.

Suha has her car repaired by young Said (Kais Nashef), and takes a liking to him. Said's childhood friend Khaled (Ali Suliman) loses his job, and has little to do except spend time with activists from an un-named group. Khaled has enlisted Said to join him on a mission.

For Khaled, the suicide mission to Tel Aviv is about faith and resistance. For Said, there are much deeper wounds. At age 10, Said learnt of his father being executed by the 'Resistance' for acting as an agent for the Israel's Shin Beth agency. Said and his family have been living that shame ever since.

When Said asks his mother (Hiam Abbass) to tell him about his father. She brushes off his question with: 'Whatever he did, he did for our benefit. May God have mercy on him.'

Perhaps more powerful than the characters are the images of Nablus itself. This really does seem like hell-on-earth — dirty water, no jobs, checkpoints, humiliating searches, air raids, concrete everywhere.

The film captures the daily struggles of Palestinians — the human side of the conflict between Arab and Israeli — rather than the de-humanising depiction of leaders, press conferences and political statements we usually see in our world of sound bites. In one scene, Said asks Khaled why one of their uncles limps. Khaled casually tells the story of the first Intifada, when Israeli soldiers asked the uncle which leg he would like to keep before disposing of the other leg using machine gun fire and boots.

This is depressing stuff. But for me, as a Muslim, the most depressing thing was the raw cynicism of the organisers of the suicide mission. These two men, known in the film by the title 'Abu' ('Father of'), clearly had little faith in what they were doing, but were happy to send depressed and disheartened young people to their deaths.

So why did these young boys decide to kill themselves? Was it a wish for martyrdom? Was it to have their posters pasted on the walls of Nablus?

After the film, my friend and I discussed Said and Khaled's motivation. For my friend, it was a case of hopelessness combined with depression and despair, soaked in injustice and oppression.

For me it was all these things manipulated by warped theology. The boys were told they were fighting for their homeland. They were reminded about the horrors of the Israeli occupation, and the hypocrisy of the Palestinian bourgeois chardonnay-socialists, as represented by the character Suha.

While the selfish hypocrisy of the 'Islamist' ringleaders was clear, the luxuriant hypocrisy of Suha, whose overseas travel and ostentation represent all that is corrupt and wrong with the Palestinian Left (and the Left in general), was also glaring. Suha's attempts to convince the boys away from their mission were so unconvincing as to be almost farcical. Her empty political rhetoric and ideological mantras could do little to erase the pain these boys felt.

Socialism is no match for mysticism. But tragically, the indigenous Islamic mysticism of the Palestinian boys had been hijacked by the 'Islamicists'. This mysticism focussed on revenge and hatred.

Instead of fighting for real Islam, these boys were sucked into the world of fraudulent Islam which taught them to blow themselves up and kill civilians.

That same fraudulent Islam was exceptionally convenient when used to fight the West's proxy war against the Soviets in Afghanistan during the 1980s. But when Osama ceased being bin-Reagan and returned to being bin-Laden, this fraudulent Islam became the excuse to demonise the true mainstream Sufi Islam.

Had these two young boys been given a proper grounding in the works of jurists and mystics like Abdul Qadir Jilani and others, perhaps they would have recognised the fraudulent nature of the 'Abu' brigade's message. But it's easy for me sitting in my comfortable middle-class Sydney home to speculate. I have no idea what it is like to live in a shanty town surrounded by hostile Jewish religious fanatics and brainwashed by Muslim religious fanatics.

The theology of hate is not what I was taught. And it is my responsibility and the responsibility of all those who claim to be liberal to ensure that our future generations are not infected with neo-Conservatism, whether of the Muslim or Judeo-Christian variety.

(First published in New Matilda on Wednesday 7 December 2005.)