In April 2005, a young Sydney sheik from a youth centre in Liverpool in South-Western Sydney found himself in hot water. Sheik Feiz Mohamed delivered a lecture some months before and was recorded as having said that women who dress in a certain way were “eligible for rape”.

Within days, the Sheik ended up offending Muslim women in particular. He attempted to clarify his remarks by saying he was only referring to Muslim women who do not wear headscarves. In essence, he was potentially justifying sexual violence being committed against the vast majority of Muslim women in Australia.

The tabloid media have had a field day, making much of the fact that some 4,000 young Muslims are members of his centre. What they don’t point out is the context within which this and other Muslim youth centres operate.

Since the 7 July terror attacks on London, there has been plenty of focus on Muslim youth (and, to a lesser extent, on converts). All available evidence shows that the London attacks were the work of ‘home-grown’ British Muslims influenced by the radical teachings of politicised religious figures. Naturally, governments and the broader community have sought reassurance from Muslim community leaders that such attacks are unlikely to occur in Australia.

However, that assurance was not provided with sufficient urgency. For instance, the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC) took some 21 days to issue a written condemnation of the London attacks.

The situation was different in Victoria, whose Islamic Council issued a stern condemnation of the attacks within less than 2 hours. So why are Victorian Muslims different from the rest of the country?

Some two years back, the Islamic Council of Victoria (ICV) executive was the subject of a quiet but effective takeover. It was a bloodless coup which brought 2nd and 3rd generation Muslims to take on leadership positions. This group of intelligent, educated and savvy operators came from a variety of grassroots youth and women’s organisations. They shared a commitment to developing a genuine Australian Islamic identity, even if it meant possibly sacrificing certain cultural orthodoxies their parents’ generation took for granted.

The ICV is unique in this regard. The situation isn’t as good in other states. In New South Wales, there are three Islamic councils competing for influence and government funds. The national body, AFIC, is currently being managed by a court-appointed administrator after warring factions wasted thousands of community dollars on expensive litigation. AFIC has also tried to litigate against other state councils (including Victoria) in an attempt to enforce more compliant executives.

Meanwhile, many Australian mosques are languishing, their executives dominated by middle-aged migrant men who want their mosques to resemble mosques in the home country just before they left. Most mosques are just ethnic cultural artefacts, their services held in Arabic and just about any language other than English. It is common for mosques to be dominated by one ethnic or linguistic group, to the exclusion of other groups.

The increased scrutiny of Islam and Muslims by media and political leaders has ensured a steady rise in the number of young people from nominally Muslim backgrounds gaining a fresh interest in their religious heritage. Naturally, the first place these people look to is the mosque their parents attend. For many, especially women, this first impression isn’t a positive one.

Mosque elders and imams frequently bar women (even those modestly dressed) from entering the mosque. Imams rarely are able to speak the language virtually all young Muslims speak – English. The few who can speak English are unable to understand the struggles young people face living life on a cultural pendulum.

Some young people have taken matters into their own hands. In 1985, I attended my first national Muslim youth camp. Until that time, I was unaware that Muslims existed anywhere outside the Middle East or my parent’s homeland in the Indian sub-Continent. A group of young people had gotten together to form the Islamic Youth Association of NSW (we called it the IYA).

We organised activities for young people – picnics, study circles, cultural nights and camps. Many elders complained. Some accused us of being irreligious by allowing boys and girls to mix. Others were worried their children might insist on marrying someone outside their culture.

Sadly, with very few exceptions, we could not rely on leaders of religious organisations or imams for support. Most of these people felt threatened by our presence, especially organisations receiving government funding to organise activities we held on a self-funded basis. It was as if we were “showing them up”.

Some of our young people could see the problem and wanted to become imams. Sadly, many could not afford to study in mainstream institutions in Malaysia or other countries. For these people, one way out was to obtain a scholarship to study in Saudi Arabia. Unfortunately, many of those who took up the offer came under the influence of Saudi Arabia’s fringe Wahhabist theology which regards both mainstream Sunni and Shia Islam as heretical.

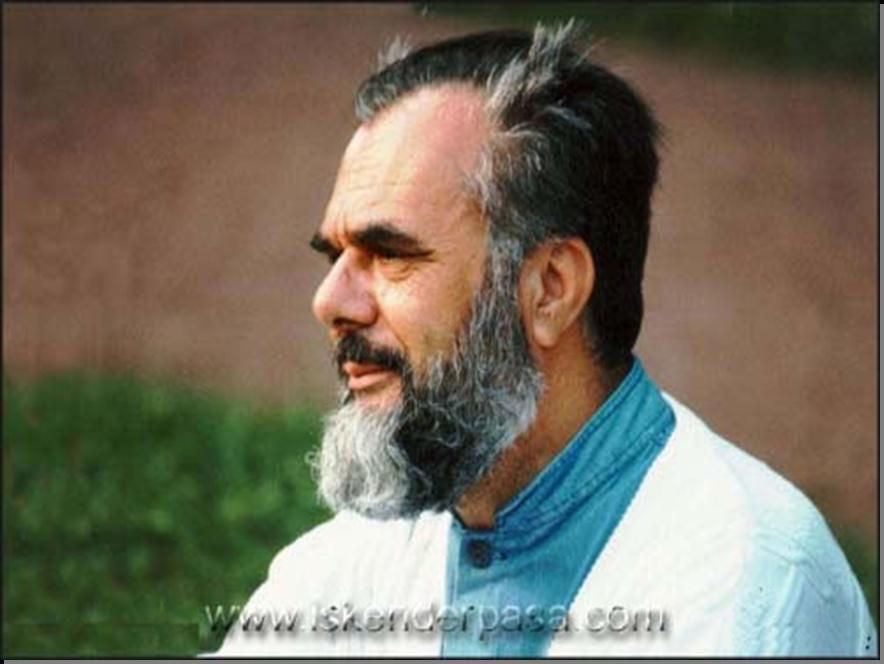

Sheik Feiz is one of these people. The views he espouses are reflective of the fringe teachings of certain Saudi religious authorities. However, it would be foolish to judge his centre – the Global Islamic Youth Centre (GIYC) – as inherently dangerous. The GIYC provides facilities that few mainstream mosques in the area provide – indoor sports, fitness classes for men and women, internet access. Those managing the GIYC are sincere young people providing services to people of their own age, people that many mainstream Muslim organisations had written off.

If I lived in Liverpool and my son had a problem with drug addiction, I doubt any of the imams of mainstream mosques could help me. But I know Sheik Feiz could. For a start, he can speak my son’s language. Further, Sheik Feiz grew up in Australia and hence understands the realities of peer group pressure and the allure of drugs.

I don’t like Sheik Feiz’s theological leanings. I certainly find his expressed views on women, Jews and martyrdom abhorrent. But the reality is that centres like Feiz’s are providing services to young people. That’s more than I can say for the middle aged migrant men whom the Prime Minister prefers to consult on Islamic community matters.

© Irfan Yusuf 2007

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Putting the GIYC into perspective ...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Thank you for the excellent piece!

Post a Comment