Recently a famous South African gentleman died. He had become a household name across the Islamic world, travelling and lecturing widely. His early speeches in South Africa and overseas included calls to end apartheid in his homeland, and criticisms of enforced racial segregation.

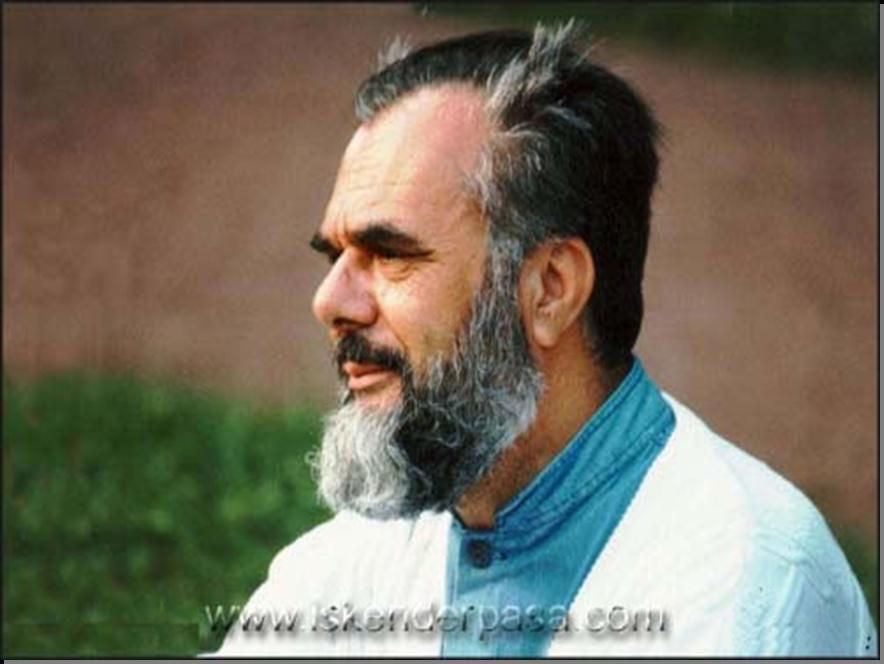

Yet the politics of apartheid wasn’t the main concern of the late Ahmed Deedat. Indeed, his main occupation was to discredit Christian theology. Despite not attending university, he was exceptionally well-read and was a fearsome debater. Some of his more crude book titles included “The God Who Never Was” and “Crucifixion or Cruci-fiction?”. Charming.

I grew up reading Deedat’s books and watching his debates with evangelical Christians in various countries. Deedat’s style was confrontational, and he frequently ran rings around those unfortunate enough to find themselves on the opposite side of him.

Deedat believed Islam was the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Despite his in-your-face and abrasive style, Deedat was motivated by a desire to share his truth with others so that they might benefit from it.

Christianity and Islam are both missionary religions. Both faiths believe they have a monopoly over the truth. Both want to share their version of truth with others. Both compete in seeking converts.

It is therefore natural that leaders of both faiths will from time to time address their minds to the faith of their competitors. Sometimes this takes the form of criticism or of focussing on a group’s perceived weaknesses.

Indeed, one of Ahmed Deedat’s last public acts was to challenge the late Pope John Paul II to a debate in Vatican Square. Thankfully the Pope had other more pressing issues to deal with.

I find it strange that religious and political leaders of Muslim-majority countries are up in arms about recent comments of the new Pope. Perhaps their frustration is a reflection of the fact that they don’t expect Christian leaders to criticise the Islamic faith. Or perhaps the leaders are concerned about some Muslims behaving in the same manner as they did in response to the Danish cartoons.

There were times when Christians and Jews would feel speaking and writing against Islam. Ironically these were times when Muslims ruled much of the known world. One precedent in Islamic Spain can explain this.

Spain was home to a physician and religious scholar named Sheik Musa bin Maymoun. Sheik Musa spoke and wrote in Arabic. One of his many treatises was a work entitled (in English) “Guide to the Perplexed”. In this book, Sheik Musa sought to compare the three Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Sheik Musa’s conclusion was clear. Judaism was superior to its sister Abrahamic faiths.

The Muslim response? Muslims who disagreed with Sheik Musa’s views did so by writing responses. Spanish Muslims still consulted Sheik Musa’s expertise in medicine. Sheik Musa himself wasn’t attacked, and copies of his book were not burnt until Catholic armies took back Muslim Spain. Burning books was too uncivilised for those polished and proud Muslims.

Sheik Musa was in fact the great Andalusian rabbi Maimonides. His critique of Islam, together with his skills as a physician, led the Kurdish general Saladin to appoint him as chief medical officer to the army that eventually conquered Jerusalem from the Frankish crusader kings. Maimonides went onto become one of Saladin’s closest and most trusted advisers.

Islam was robust and strong enough in those times to withstand criticism. Muslims were sensible and educated and civilised and confident enough to be able to accept criticism. They could debate their critics on an intellectual level without having to resort to violence or being highly strung and reactionary to even the mildest rebuke.

I once surprised a Catholic priest with a range of questions. This priest had made public statements to the effect that the Koran preaches violence. I asked him whether he could read Arabic, given that the Koran was in Arabic. He said no. I asked him which translation he used. He said he couldn’t remember. I listed some 10 translations to him. He still couldn’t answer. In the end he became defensive.

In an environment as free as Australia, a humble layman like myself can expose the relative ignorance of a cardinal. I could do this using intellect and logic, far more powerful tools than defensiveness or threatening violence.

Muslims offended by the Pope’s comments about Islam and history are better off addressing these arguments than condemning the Pope. If Muslims become defensive or even hint at violence, they will merely be personifying (and thus confirming) of the Pope’s claims.

It’s only to be expected that the leader of a missionary faith will criticise other missionary faiths. Just as we expect Don Brash to criticise Helen Clark or Kim Beazley to criticise John Howard. Thankfully, clerics tend to be more polite than politicians most of the time. But criticism is part of the Abrahamic tradition.

If you can’t stand the missionary heat, you should think about getting out of Abraham’s spiritual kitchen.

© Irfan Yusuf 2006

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Infantile Muslim responses to the Pope's latest fatwa

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)